For several years I taught on a campus that had an ESL program. We had students from around the globe. Families literally sought out our school before signing a lease or purchasing a home because they wanted to be sure their kids would be zoned to our campus. Our program was well known for the success we had with multilingual children.

Even though the majority of the teachers on our campus were monolingual, we nurtured a mindset that embraced students’ assets-all of them and not just their English assets. On our campus, we worked hard to be student-centered.

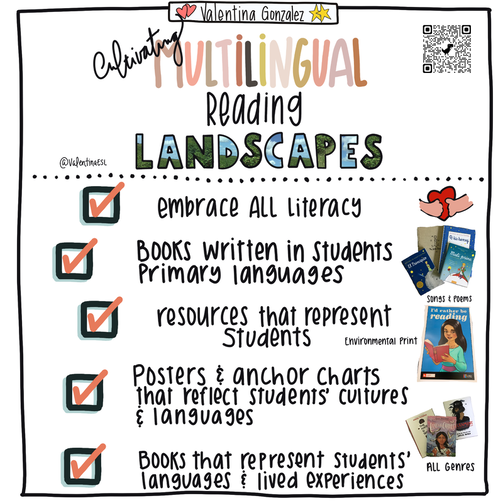

All literacy was valued. Since our students came to us from around the globe, we were fortunate to learn from their lived experiences, backgrounds, and families. Each of them was unique. Building relationships with students and between students allowed us to uncover their many gifts. Some of our students could speak, read, and write in multiple languages! Others heard another language at home. The languages and literacies our students brought with them to school were used as springboards towards new learning that happened in our classrooms.

The more we capitalized on students’ language funds, the more we realized the value of books in the languages they speak. We took a look at our students and began to work towards aligning the literature we offered. It was important that the books students had access to paralleled the “customers” who needed them. Our customers were our students. This task was not always easy. Finding quality books in languages other than English is challenging. One way we did this was through partnerships with the school media specialist (librarian).

Not only did we want students to have books in the languages they spoke, but we also wanted our learners to pick up books and connect with the characters and experiences. This meant we needed books that students from around the world could see themselves in, or as Rudine Sims-Bishop calls them, books that are mirrors. This was equally as challenging because many of the books that we had seemed to represent our students but after careful analysis, these books misrepresented cultures, were stereotypical, or lived at the surface level. We needed quality. As a greater number of educators understand the need for books that represent diverse students, more culturally inclusive books are being published.

Our multilingual landscape included the classroom walls. We took an audit of the space our students spent their days working in and we thought about what this space communicated, what it valued, and what was left out. Then we took action towards creating spaces that lifted students up, embraced and valued all learners, and cultivated a love for languages and literacies. We did this by:

Multilingual readers don’t leave their identity, their language, and cultures at home. These are powerful tools that we use to help students grow beautiful, healthy reading lives. EVEN in ESL programs we CAN honor, affirm, & value students’ language & literacy. It may look & sound a bit different from bilingual programs, but we can do it! Kids should not have to shed their primary language when they walk into the classroom. It’s an asset!

If you like what you read and would like to read more about teaching multilingual children to read and write, you may enjoy the book Reading & Writing with English Learners: A Framework for K-5 by Valentina Gonzalez and Dr. Melinda Miller.

All literacy was valued. Since our students came to us from around the globe, we were fortunate to learn from their lived experiences, backgrounds, and families. Each of them was unique. Building relationships with students and between students allowed us to uncover their many gifts. Some of our students could speak, read, and write in multiple languages! Others heard another language at home. The languages and literacies our students brought with them to school were used as springboards towards new learning that happened in our classrooms.

The more we capitalized on students’ language funds, the more we realized the value of books in the languages they speak. We took a look at our students and began to work towards aligning the literature we offered. It was important that the books students had access to paralleled the “customers” who needed them. Our customers were our students. This task was not always easy. Finding quality books in languages other than English is challenging. One way we did this was through partnerships with the school media specialist (librarian).

Not only did we want students to have books in the languages they spoke, but we also wanted our learners to pick up books and connect with the characters and experiences. This meant we needed books that students from around the world could see themselves in, or as Rudine Sims-Bishop calls them, books that are mirrors. This was equally as challenging because many of the books that we had seemed to represent our students but after careful analysis, these books misrepresented cultures, were stereotypical, or lived at the surface level. We needed quality. As a greater number of educators understand the need for books that represent diverse students, more culturally inclusive books are being published.

Our multilingual landscape included the classroom walls. We took an audit of the space our students spent their days working in and we thought about what this space communicated, what it valued, and what was left out. Then we took action towards creating spaces that lifted students up, embraced and valued all learners, and cultivated a love for languages and literacies. We did this by:

- displaying student work,

- co-creating anchor charts,

- including students’ spoken languages, and

- using images that included students’ cultures and lived experiences.

Multilingual readers don’t leave their identity, their language, and cultures at home. These are powerful tools that we use to help students grow beautiful, healthy reading lives. EVEN in ESL programs we CAN honor, affirm, & value students’ language & literacy. It may look & sound a bit different from bilingual programs, but we can do it! Kids should not have to shed their primary language when they walk into the classroom. It’s an asset!

If you like what you read and would like to read more about teaching multilingual children to read and write, you may enjoy the book Reading & Writing with English Learners: A Framework for K-5 by Valentina Gonzalez and Dr. Melinda Miller.